Hypertrophy describes how muscle fibers enlarge in response to resistance stress, driven by mechanical tension, metabolic strain, and cellular signaling such as mTOR. The process combines microdamage repair, protein synthesis, and energy system adaptation, shaped by training variables and nutrition. Understanding these mechanisms clarifies why some programs succeed and others stall, and it points toward practical strategies that follow.

What Is Hypertrophy and Why It Matters

Hypertrophy is the enlargement of muscle cells driven primarily by resistance training, during which repeated overload causes microtears in muscle fibers that are rebuilt larger during recovery.

It describes muscle growth through increased myofibrillar content and, alternatively, expanded sarcoplasmic volume, both improving strength and appearance.

Effective protocols emphasize 6–12 repetitions per set with sufficient weekly volume—often 30–40 sets per muscle group—and training each muscle at least twice weekly to balance stimulus with recovery.

Nutrition and genetics modulate outcomes: protein intake supports muscle protein synthesis, while genetic variation affects fiber composition and adaptive capacity.

Understanding hypertrophy helps prioritize program design, recovery scheduling, and dietary strategies to maximize muscle fibers’ adaptive enlargement without overtraining.

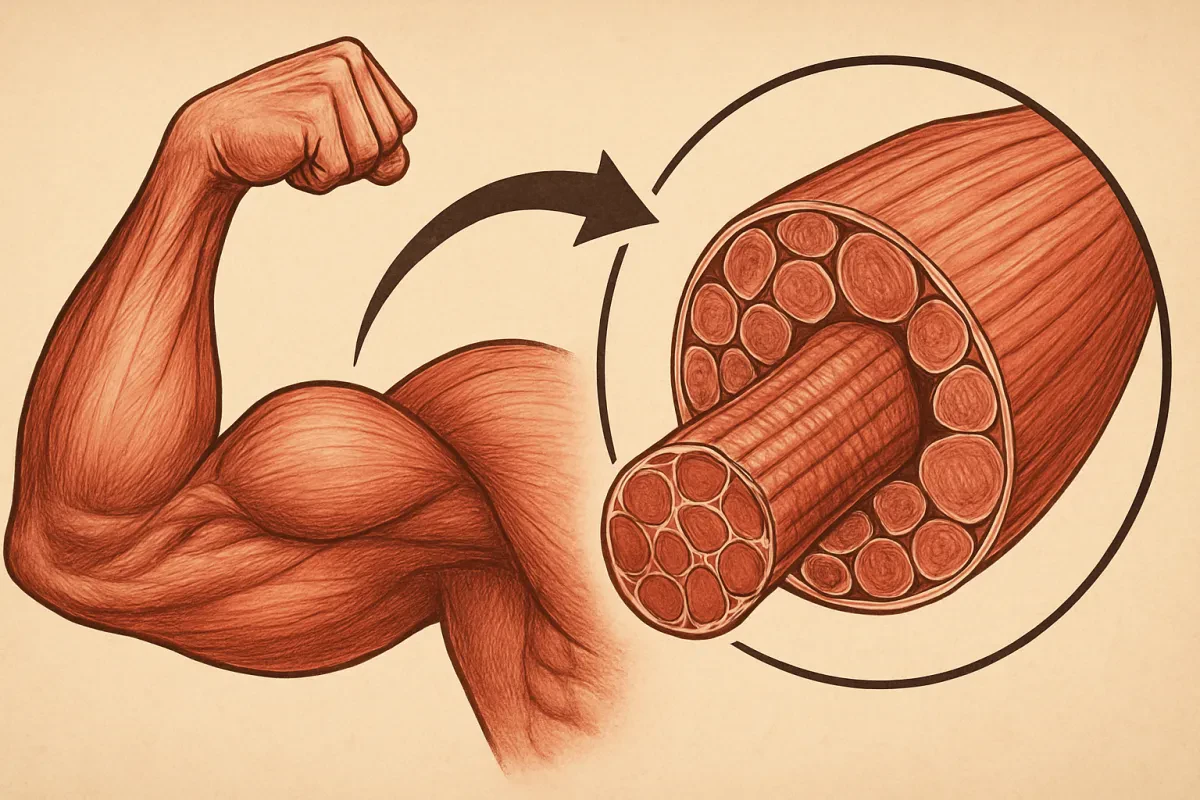

The Cellular Mechanisms Behind Muscle Growth

Because resistance training imposes mechanical tension and metabolic stress on muscle fibers, a cascade of cellular events unfolds that increases fiber size.

Mechanical tension and eccentric-induced microdamage trigger signaling pathways (notably IGF-1 and mTOR) that upregulate synthesis of contractile proteins actin and myosin, driving hypertrophy.

Metabolic stress amplifies anabolic signaling via accumulation of metabolites, cell swelling, and hormonal responses.

Dormant satellite cells activate in response to damage, proliferate, and fuse with existing fibers, donating myonuclei that support greater protein synthesis capacity and sustained growth.

Genetic factors modulate fiber-type distribution and signaling efficiency, influencing individual hypertrophic potential.

Together these mechanisms—protein synthesis, satellite cell contribution, and metabolic and mechanical stimuli—produce durable increases in muscle fiber cross-sectional area.

Types of Hypertrophy: Myofibrillar Vs Sarcoplasmic

Muscle growth can take distinct forms depending on the stimulus: myofibrillar hypertrophy enlarges and adds contractile proteins (actin and myosin) within fibers, improving strength and force production, while sarcoplasmic hypertrophy increases the volume of the sarcoplasm and energy stores, enhancing work capacity and endurance.

Myofibrillar hypertrophy emphasizes increased myofibril size and number, translating to greater muscle strength and improved contraction efficiency; it is commonly pursued by athletes in strength sports.

Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy expands non-contractile fluid, boosting glycogen and ATP reserves to support higher-repetition efforts and prolonged activity.

Resistance training can bias adaptations toward one form or the other. Coaches and trainees manipulate training variables to prioritize functional strength, metabolic capacity, or a balance suited to athletic or aesthetic goals.

Key Training Variables: Tension, Volume, and Load

Training outcomes hinge on manipulating three core variables—mechanical tension, training volume, and load—each of which targets distinct physiological pathways that drive fiber adaptation.

Mechanical tension from lifting heavy loads activates signaling that promotes muscle protein synthesis, making tension a primary stimulus for hypertrophy.

Training volume, quantified as total weight lifted across sets and reps, correlates with growth; recommended weekly targets often fall around 30–40 sets per muscle group to maximize stimulus.

Load intensity between roughly 67–85% of 1RM paired with moderate rep ranges (6–12) effectively balances tension and volume.

Rest intervals should be tailored: shorter rests favor metabolic contributions, longer rests support heavier multi-joint efforts.

Progressive overload—systematic increases in load or volume—remains essential to sustain adaptation.

The Role of Muscle Damage and Metabolic Stress

Several forms of tissue disruption and metabolic accumulation combine to drive hypertrophy: eccentric-induced microtears stimulate repair pathways while metabolite buildup (for example, lactate and hydrogen ions) promotes hormonal and cellular responses that support growth.

Muscle damage from intense resistance training activates inflammatory and satellite cell processes that aid remodeling, increasing fiber cross-sectional area.

Intense resistance training triggers inflammation and satellite cell activity that remodels muscle, expanding fiber cross-sectional area.

Concurrently, metabolic stress—accumulation of metabolites during anaerobic efforts—enhances cellular swelling and endocrine signals that further stimulate protein synthesis.

The interaction of mechanical tension, damage, and metabolic fatigue creates a favorable environment for hypertrophy without implying damage as the sole driver.

Effective resistance training balances these stimuli to maximize adaptive signaling while allowing recovery, since elevated protein synthesis persists post-exercise and underpins the repair and hypertrophic response.

Programming for Hypertrophy: Reps, Sets, and Frequency

When structuring a hypertrophy program, practitioners should prioritize moderate rep ranges (roughly 6–12 per set), multiple sets (typically 3–6 per exercise), and total weekly volume of at least 10 sets per muscle group, distributed across a minimum of two weekly sessions to maximize syntheses of muscle protein.

Programming for hypertrophy balances reps, sets, and frequency to produce mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and sufficient recovery. Training volume drives adaptation; beginners may start at the lower end while advanced trainees increase sets. Rest intervals of 30–90 seconds complement hypertrophy-focused work.

Frequency of hitting each muscle group twice weekly elevates cumulative protein synthesis compared with once-weekly approaches. Including compound and isolation movements optimizes fiber recruitment and overall development within an evidence-based training volume framework.

Nutrition Strategies to Support Muscle Growth

Although resistance training provides the stimulus for muscle growth, nutrition determines how effectively that stimulus is converted into larger fibers; adequate protein (1.6–2.2 g/kg/day) distributed in 20–30 g servings with 2–3 g of leucine per meal, a modest caloric surplus (≈200–400 kcal/day), and sufficient carbohydrates (3–7 g/kg/day) to replenish glycogen are foundational for maximizing hypertrophy.

Effective nutrition strategies prioritize protein intake to support muscle protein synthesis, spacing meals to maintain amino acid availability. A controlled caloric surplus supplies energy for repair and growth without excessive fat gain.

Carbohydrates fuel high-intensity resistance work and restore glycogen between sessions. Practical application involves planning meals with quality protein sources, carbohydrate portions aligned to training load, and modest energy excess tailored to individual progress.

Recovery, Sleep, and Hormonal Factors

Recovery, sleep, and hormonal regulation collectively determine how effectively muscles repair and grow after resistance training.

Recovery allows damaged myofibrils to be rebuilt and enlarged; typical repair windows around 48 hours optimize protein synthesis and subsequent muscle hypertrophy.

Sleep quality directly affects this process: less than seven hours reduces anabolic signaling, lowering protein synthesis and impairing recovery.

Hormonal factors modulate outcomes—elevations in testosterone and growth hormone support repair and stimulate protein accretion, while chronically high cortisol inhibits synthesis and promotes breakdown.

Adequate nutrition, especially protein at 1.6–2 g/kg, supports hormonal balance and recovery, enhancing hypertrophic adaptation.

Managing stress, prioritizing sleep, and scheduling training to permit recovery are thus essential for maximizing muscle hypertrophy.

Individual Differences: Genetics and Fiber Types

Beyond sleep and hormones, innate biological differences shape how individuals respond to the same training stimulus.

Genetics account for roughly half the variance in muscle mass and substantially affect muscle fiber types distribution, influencing hypertrophy potential. Fast-twitch fibers (Type II) generally exhibit greater growth capacity than slow-twitch fibers (Type I), and muscles rich in fast-twitch fibers—such as pectorals, biceps, triceps, and lats—tend to enlarge more readily under resistance training.

Genetic factors also govern shifts between Type IIx and IIa fibers but do not convert Type II into Type I.

Additionally, myostatin functions as a negative regulator: reduced myostatin activity, whether genetic or pathological, permits enhanced muscle fiber growth and markedly increases hypertrophy potential compared with typical regulation.

Practical Hypertrophy Workouts and Progression Methods

Designing practical hypertrophy workouts centers on balancing volume, intensity, and frequency to elicit consistent progressive overload while allowing recovery.

Programs for muscle hypertrophy commonly use 6–12 repetitions per set, 60–90 seconds rest, and a weekly target of 30–40 sets per muscle group.

Aim for 6–12 reps, 60–90 seconds rest, and about 30–40 weekly sets per muscle group.

Training for hypertrophy blends compound lifts (squats, bench presses) with isolation movements to recruit varied fibers.

Progressive overload is implemented by systematically increasing load, reps, or sets, and by methods like eccentric overload to amplify mechanical tension and damage.

Training frequency of at least twice weekly per muscle group optimizes stimulus and recovery.

Careful tracking of volume and intensity, adequate protein intake, and individualized adjustments guarantee sustainable muscle growth.

Conclusion

Hypertrophy unites cellular repair, mechanical tension, metabolic stress, nutrition, and recovery into a coherent process that sculpts strength and form. Recognizing the interplay of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic adaptations, alongside individual genetic limits, empowers purposeful training choices. Could one imagine muscles as living blueprints, rewritten by each rep and meal? With strategic programming, progressive overload, adequate protein, and sleep, consistent small decisions translate into measurable growth and enduring performance.